Well, the community of Geminis is the most consistently in tune with what their spirit is telling them to do or why they have breath in their lungs.

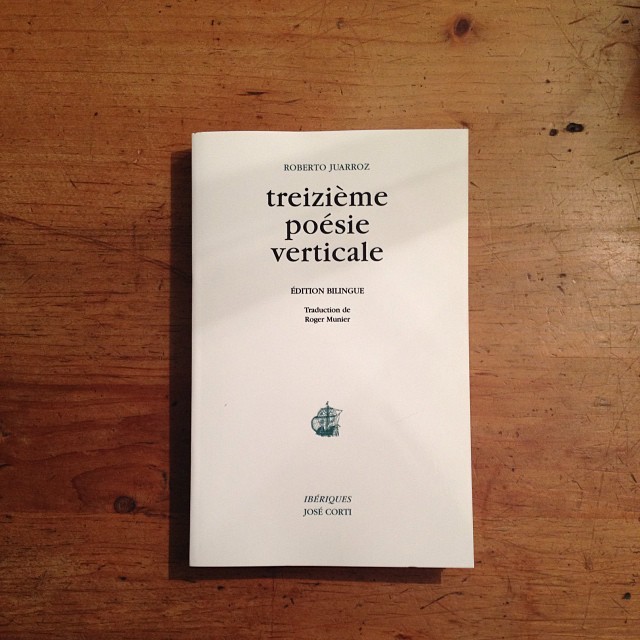

“A time when a man put out to sea ceased to exist”→

Which is why Steinbeck’s words are so interesting to me. It seems that in the past, there were large parts of your identity you were forced to leave behind when you traveled, and in the absence of those things, not only did other people forget you, but you forgot yourself. And rather than being a entirely negative thing, maybe this had the effect of softening that identity, of making you define yourself less from the books you’d read or the connections you’d had with others. Maybe one of the side effects of travel, and for some the main objective, was and still is to peel back some of those layers of identity, so that you can see that the whole notion isn’t built on anything solid or fixed to begin with. And maybe if you see your identity as less fixed, then you’re more open to change, to reinvention, more open to the world as it crashes down on the shore at your feet.

Identity’s not so much a kernel we carry inside us as the intersection of all our links and connections. Travelling is always an occasion of finding a different aspect of oneself, through interacting with the unfamiliar.

At home in our interpreted world.

We are the music-makers.

And we are the dreamers of dreams,

Wandering by lone sea-breakers,

And sitting by desolate streams;

World-losers and world-forsakers,

On whom the pale moon gleams;

Yet we are the movers and shakers

Of the world forever, it seems.

User Expertise Stagnates at Low Levels→

Decades can pass with even frequent system users barely learning one or two new things per year.

This means that enhancing the discoverability of existing features sometimes trumps the need for new features, as in the case of Office 2007:

Ensuring that people understood the old features was more important than adding new ones.

Get along with it:

You’re unlikely to be the first user interface in 30 years for which all users become sophisticated experts and learn all the features.

Buttersafe – Name that monster

“Like a ghost, it haunted me with restless sorrow, but it didn’t have any purpose.”

Hoy no he hecho nada.

Pero muchas cosas se hicieron en mí.

Un mot et tout est sauvé. Un mot et tout est perdu.

J’ai chaud. J’ai froid. Quel mot sera assez puissant pour effacer tout un corps d’homme et renverser la situation ?

How I Met Your Mother, by Ta-Nehisi Coates→

Varg Vikernes, génie et part d'ombre du black metal→

Du pain bénit pour les journalistes qui écriront plus tard à son sujet. Seulement voilà, Kristian a une grille de lecture plutôt originale de la géopolitique de la Terre du Milieu. Pour lui, hobbits, elfes et nains incarnent le rouleau compresseur de la chrétienté à l’origine de la destruction des pratiques ancestrales païennes, alors que les armées de Sauron sont en fait les good guys, de valeureux Vikings qui ne cherchent qu’à défendre et étendre leur territoire.

En toute logique, Kristian renomme son premier groupe, Kalashnikov, en Uruk-Hai (une race d’orques guerriers dans le Seigneur des Anneaux), avec des paroles aussi inteligentes que «Uruk-Hai / You will die!». Rebaptisé Varg («loup» en norvégien) pour l’occasion, il rejoint Old Funeral, formé par les futurs membre de Immortal.

Mais voilà, le death metal bas du front et plein de clichés, Varg Vikernes, 18 ans à peine, l’exècre. Les clubs technos de Bergen l’intéressent bien plus que les vestes à patchs. Sobre, il se met à rôder silencieusement dans ces lieux pour s’imprégner des vibrations et de la puissance froide et répétitive de la musique électronique.

Comment la critique des « bobos » est passée à droite→

Il convient de réfléchir aux effets idéologiques de dix ans de captation d’un terme utilisé au départ par des journalistes en quête de sujets légers pour les rubriques « Société ». La dénonciation du bobo est aujourd’hui une manière facile et faussement audacieuse de stigmatiser l’anti-racisme et le combat contre toutes formes de discrimination. Des causes auxquelles le peuple, le « vrai », serait profondément allergique.

Rowling and “Galbraith”, an authorial analysis→

I was approached by a reporter, Cal Flyn, from the Sunday Times, to assess this kind of variation in the writings of “Robert Galbraith,“ a first-time novelist and author of The Cuckoo’s Calling. (I learned later from the papers that the paper had received an anonymous tip via Twitter that Galbraith was the pen name of J.K. Rowling. And in retrospect there were a lot of other clues as well. For example, Galbraith apparently was surprisingly good at describing women’s clothing, possibly suggesting a female author.) Would I be willing to look into this? I said yes, of course, but with a couple of conditions. First, I needed clean (machine readable) copies of Cuckoo, and clean samples of something comparable undisputedly by Rowling herself. Secondly, I needed other comparable samples from other writers (distractor authors, to use the common term) to assess the degree of variation.

(via lkm)

“And I’m always a little sorry for them, heavy beings, big ones, to hear how they snore and dream aloud and are so very much alone.”

A behind the scenes look at McNulty, Kima, Bunk, and Omar→

“The ancients valued tragedy, not merely for what it told them about the world but for what it told them about themselves,” he said. “Almost the entire diaspora of American television and film manages to eschew that genuine catharsis, which is what tragedy is explicitly intended to channel. We don’t tolerate tragedy. We mock it. We undervalue it. We go for the laughs, the sex, the violence. We exult the individual over his fate, time and time and time again.”

In his Baltimore version of Olympus, the roles of gods were played by the unthinking forces of modern capitalism. And any mortal with the hubris to stand up for reform of any kind was, in classical style, ineluctably, implacably, pushed back down, if not violently rubbed out altogether.

“That was just us stealing from a much more ancient tradition that’s been so ignored, it felt utterly fresh and utterly improbable,” he said. “Nobody had encountered it as a consistent theme in American drama because it’s not the kind of drama that brings the most eyeballs.” It was possible in this time and place because, in the new pay cable model, eyeballs were no longer the most important thing.

And on how the magic happens:

Yet The Wire was also inescapably modern; its characters operated based on real, idiosyncratic psychologies, refusing to be pushed around like figures on a board. Sometimes they surprised even their creators. One passionate argument in the writers’ room was about a major moment in Season 1’s next-to-last episode, “Cleaning Up”: the execution of the young drug slinger Wallace by the tougher, only slightly older thug Bodie Broadus. Just before shooting his friend, Bodie hesitates, gun shaking. Ed Burns, the co-creator of the series, raised an objection: The Bodie we had seen to that point, he argued, was the very incarnation of a street monster, a young person so damaged and inured to violence by the culture of the drug game that he would never hesitate to pull the trigger, even on a friend.

“It didn’t go with the character. Bodie was a borderline psychopath almost. I was like, ‘We’re leading the audience down this path, and now this guy is backing off?’ That’s fucked up. That’s bullshit,” he said, remembering his feelings on the scene.

In future seasons, though, Broadus would emerge as the drug game’s answer to the rogue detective Jimmy McNulty: a soldier who tries to make his own way and ends up ground down by the system. His death would be unexpectedly poignant. All of that, Burns granted, was set up by his unexpected moment of humanity in Season 1.

“What it did was it allowed for a wonderful dynamic that went on for four seasons. It brought out a lot of comedy that psychopaths don’t have,” he said. “It was a learning curve for me. Originally I just didn’t like it because you don’t pull punches like that with the audience. Now, when I think about it, I think, ‘This is cool. This is something that allowed for another dimension.’ It worked. It worked fine.”

“Like I say, I’m a minimalist in a rapper’s body”→

I want to tell people, “I can create more for this world, and I’ve hit the glass ceiling.” If I don’t scream, if I don’t say something, then no one’s going to say anything, you know? So I come to them and say, “Dude, talk to me! Respect me!”

Yeah, respect my trendsetting abilities. Once that happens, everyone wins. The world wins; fresh kids win; creatives win; the company wins.

I think what Kanye West is going to mean is something similar to what Steve Jobs means. I am undoubtedly, you know, Steve of Internet, downtown, fashion, culture. Period. By a long jump. I honestly feel that because Steve has passed, you know, it’s like when Biggie passed and Jay-Z was allowed to become Jay-Z.

Le mystère Bush→

« …un monde de solitude peuplé de chiens mélancoliques. »

Le sentier des pêcheurs (Gorges du Verdon).

If Engelbart

If Engelbart had been understood and followed, the trade of work I’m in would have been considerably different. Instead of building interfaces for perpetual re-beginners, instead of an elusive search for intuitiveness and the perfect first impression, we would have focused on the long term relationship between people and machines.

We wouldn’t have so many toolmakers and inventors, instead, we’d have teachers and coaches. Engelbart envisioned the manipulation of computers as an act of learning, where, simultaneously, you get better at your own skills and at using the machine, and the machine becomes more tailored to you. The tool would have been just that, an aid for the individual to delve into her work.

We wouldn’t have worried as much upon user experience, for we wouldn’t call ourselves and others “users”. For that matter, the same as we don’t call anyone a pencil user, we might have stayed with calling people writers, professors, painters and so on. And we wouldn’t feel so responsible for their experiences – for everyone understands learning experiences evolve in time, whereas computer experience in the app culture is a matter of the instant.

There are many echoes of Engelbart’s legacy in today’s computer culture. But the NLS remains a powerful neverwas and might-have-been, a pole from which we can orient and situate ourselves.

I find this beginning phase exciting and strange. A time when you’re not sure what’s going to come out of you. Pregnant, but with what sort of creature?

data's double life→

Every wave of positivism eventually comes undone, when its central contradiction emerges. The fact that the resolutely ‘anti-political’ behaviorists of the 1920s, for example, produced techniques of psychological control that could serve the interests of military and corporate power, is one demonstration of this. The NSA revelations arguably herald a similar moment of reckoning for digital data collectors and analysts. Google’s childish political mantra of being anything other than ‘evil’ ignored the historical lesson, that apolitical, purposeless knowledge is often one of the greatest assets to the strategies of the powerful.

This wilful anti-technicalism, which is a form of anti-intellectualism, mirrors the present cultural obsession with nostalgia, retro and vintage; it is boring, and we reject it.

Almost any time you interpret the past as ‘the present, but cruder’, you end up missing the point.

Sometimes.

Oui et non.

The word design

“Design thinking suggests the synthetic way in which designers are (supposed to be) thinking can be applied to almost any subject. […] Never mind the fact that there are many who would argue with the idea of design as a solution-focused activity, that this conception of design is pure ideological cant.”

— A text by Sam Jacobs about “PRISM as the dark side of design thinking”

The word “design” as a totem, as a password to so many places.

« La même envie de jeter des pierres dessus »→

Je dois fantasmer quelque chose de cette ville, comme j’ai fantasmé, fantasme et fantasmerai beaucoup d’autres cités. Il commence à pleuvoir sur North Avenue et quelque chose de flou, d’impalpable et d’indéfini flotte durant cette déambulation automobile. Baltimore joue aux montagnes russes quant à la perception que l’on peut en avoir ; elle fait évoluer nos chimères de spectateurs au fur et à mesure que l’on visite les artères qui l’irriguent.

“It’s Time to Reinvent the Personal Computer”→

An article that could have been written, point for point, in 1995, at the time where people like Nielsen were discussing the Anti-Mac interface. Same delusions about 3D, same hopes about non visual interfaces. Still, there’s so much to do with the personal computer that we haven’t tried yet.

Often when I speak with young people they ask me but if you’re so critical why do you do this job?

And I answer: I do this job because I fight for the right to think. I don’t know if the things I do are so good, if I am so good, but when I fight against all the contradictions that my projects raise then I understand the world – that’s it.

Pendant ce temps là

Trois ans presque depuis le dernier billet de ce carnet. J’ai arrêté ma thèse il y a deux ans pour me lancer à plein temps dans la conception d’interfaces et de dispositifs numériques, comme quoi. Je profite de cet anniversaire pour publier quelques travaux effectués ces dernières années qui auraient mérité d’y figuer.

- Un poster sur l'histoire de la fenêtre.

- La recension d'un livre sur Art & internet.

- Un essai théorique sur la nature des interfaces graphiques, qui présente des idées autour desquelles je tourne encore aujourd’hui.