“With each set of three books, I’ve commenced with a sort of deep reading of the fuckedness quotient of the day,” he explained. “I then have to adjust my fiction in relation to how fucked and how far out the present actually is.”

Superstition Today

Nicolas Nova, sifting through examples of “magical thinking” in technology use:

Obadia also points out that although the concept of “superstition” is rooted in a condescending othering of “backward“ or non-Western modes of thinking, it does not mean it should be abandoned.

Examining these examples in a pragmatic way, it appears people will sometimes ascribe agency to devices when they have difficulty understanding how those devices work. And this agency giving is part of a domestication process of technology. (Sometimes, Nova argues, people’s ignorance is maintained on purpose, and “magic” is used as part of marketing discourse.)

What’s interesting in this behaviour – giving agency to technology that does not behave in predictable ways – is that it is almost never leveraged on purpose. It behaves like an unwritten script for the object, one that no designer has anticipated. It’s revealing of the wildness of machines beneath the domesticating efforts of code and design.

The political debt we hide behind technical debt

Or, further evidence of computing used as a tool for centralization.

Joseph Weizenbaum, via Audrey Watters:

I think the computer has from the beginning been a fundamentally conservative force. It has made possible the saving of institutions pretty much as they were, which otherwise might have had to be changed. For example, banking. Superficially, it looks as if banking has been revolutionized by the computer. But only very superficially. Consider that, say 20, 25 years ago, the banks were faced with the fact that the population was growing at a very rapid rate, many more checks would be written than before, and so on. Their response was to bring in the computer. By the way, I helped design the first computer banking system in the United States, for the Bank of America 25 years ago.

Now if it had not been for the computer, if the computer had not been invented, what would the banks have had to do? They might have had to decentralize, or they might have had to regionalize in some way. In other words, it might have been necessary to introduce a social invention, as opposed to the technical invention.

What the coming of the computer did, “just in time,” was to make it unnecessary to create social inventions, to change the system in any way. So in that sense, the computer has acted as fundamentally a conservative force, a force which kept power or even solidified power where is already existed.

But there are none so frightened, or so strange in their fear, as conquerors. They conjure phantoms endlessly, terrified that their victims will someday do back what was done to them—even if, in truth, their victims couldn’t care less about such pettiness and have moved on. Conquerors live in dread of the day when they are shown to be, not superior, but simply lucky.

The wealthy are plotting to leave us behind→

There’s nothing wrong with madly optimistic appraisals of how technology might benefit human society. But the current drive for a post-human utopia is something else. It’s less a vision for the wholesale migration of humanity to a new a state of being than a quest to transcend all that is human: the body, interdependence, compassion, vulnerability, and complexity. As technology philosophers have been pointing out for years, now, the transhumanist vision too easily reduces all of reality to data, concluding that “humans are nothing but information-processing objects.”

the only mofos in my circle are people that I CAN LEARN FROM. i believe THAT is the first and foremost rule to a successful life.

you are going to be as educated and successful as the 10 most frequented people you call/text on your phone

I’ll say let the phones be smart. I want to be wise. I want the courage to love. I want the courage to sacrifice. I want the courage to be nonconformist in the face of injustice. Adolf Hitler was smart. I’m not impressed by that, you see.

La consolation et la violence→

Oeil pour œil, dent pour dent, n'existe pas. Pour une violence subie, une violence faite n'a rien à voir. Ne soulage pas. Ne rembourse jamais. Ne ramène aucun mort à la vie. La colère d'Achille et son immémoriale tristesse ne se résorbent pas avec le massacre d'Hector et je crois qu'il le sait. De le savoir creuse son désespoir, et creuse son impuissance, les deux font le lit de sa violence.

Le passage à l'acte violent rend dévastatrice une pensée qui n'était violente que pour consolation. Devenue action, elle ne console de rien. Mais c'est l'enfer de la répétition que de le savoir au fond et de le faire quand même.

Fire attention economy

Something I noticed for the first time last night was how little eye contact there is around a fire. We talked to each other but we stared at the flames. It’s called soft fascination, E said, in to the fire. It happens with clouds and rustling leaves, too, a lot of things in nature. You can leave the fire and come back to it without feeling like you’ve missed something, without needing to pick up where you left off. You can tune out partially and bathe in the variant light, and at the same time hone in on specifics, like how flames in different sections can flicker at different speeds. How smoke swirls and the heat-side of a new log fissures. How the charcoals fall off the bottom and pulsate orange-red. Fire’s interesting in a different way than a TV or phone, is more a flat surface you set your attention on than a hole it falls into. Fire seems to work on its own channel, visual white noise with a little extra something.

C’est en vain que tu as compris si tu n’aimes pas ce que tu as saisi, car la sagesse est dans l’amour. L’intelligence précède l’esprit de sagesse et ne goûte que d’une manière transitoire, mais l’amour savoure ce qui demeure.

On the War on Drugs→

Johann Hari offers a pragmatic, rethought and really, downright fascinating approach to drugs and addiction.

On the forgotten roots of prohibition:

If you look at the reason why drugs are banned in the United States, and then in Britain, the real reason was a race panic. There’s a deep belief that African Americans and Chinese Americans are using drugs to attack white people, and therefore drugs have to be banned in order to put these ethnic minorities back in their place.

What to expect from the end of prohibition: less violence.

If you or I go to the local off-license [liquor store], and try to steal the beer or vodka, the owner will just call the police. He doesn’t need to be violent or intimidating. If we go up to the local coke dealer or the local weed dealer and try to steal their product, they can’t call the police, because the police will arrest them. So they do have to be violent and intimidating. The sociologist Philippe Bourgois says that prohibition creates a culture of terror. (…)

The best way to test that is to ask, where are the violent alcohol dealers today? Does Oddbins go and blow up the drinks aisle in Sainsbury’s? Do they go and shoot the people that work in the Sainsbury’s aisle in the face? Does the head of Guiness send people to go and torture the head of Smirnoff? No. But under alcohol prohibition, there were a huge number of violent alcohol dealers. Nothing’s changed about alcohol, the drug remains the same. The method of how you sell it has changed, and therefore the murder rate massively fell.

On the kind of violence prohibition has caused in Mexico:

If you’re the person who says, we won’t just kill their pregnant wives, we’ll put it on Youtube, you gain a brief competitive advantage. If you say, we’ll cut off their faces, sew their faces onto a football and send the football to their families — this is a real thing that happens — you get a brief competitive advantage.

Legalizing drugs would conceivably reduce children’s exposure and access to the market:

Legalisation is a way of imposing regulation on that, currently completely deregulated market, and one of the things you can do when you regulate drugs is put barriers between people. So, for example, no one in my nephews’ school is selling Jack Daniels or Budweiser, but there are loads of people selling weed and pills. There was a study in the United States that found that teenagers find it easier to get hold of marijuana than they do to get hold of alcohol, precisely because drug dealers don’t check I.D. So, if your main motivation when approaching the drug war, and it’s a very good one, is to say you do not want your teenagers to have access to drugs, that’s one of the strongest arguments I know for legalisation.

Funny how little the Portuguese experiment is talked about, compared to, say, the Netherlands:

One thing we can say about the drug war is that we gave it a fair shot. We gave it 100 years and a trillion dollars. We can compare the results we got from that, to the results of countries where they’ve spent most of their money on turning addicts’ lives around. In Portugal, nearly 15 years ago, they decriminalised all drugs and spent the money on treatment for addicts, and turning addicts’ lives around, in particular through subsidised jobs. The results are that injecting drug users are down by 50%, overdoses are massively down, and HIV transmission among addicts is massively down. We can see how these models work, there’s nothing theoretical or abstract about this debate anymore, there are countries that have tried the prohibitionist approach, there are countries that have tried approaches based on compassion, and we can see the results.

Ultimately:

The evidence is clear: A system based on stigma and punishment and hatred doesn’t work. A system based on compassion and care and love does work. It turns people’s lives around. So now we have a choice. Do we want to have another century of charging off in the wrong direction? Or do we want to listen to the countries where they are trying the new approach, and it is having amazing results?

When we have exterior accomplishment without the interior, that’s when, I think, we most strongly feel like we are imposters.

We become mechanized in mind, and consequently attempt to provide solutions in terms of engineering, for problems which are essentially problems of life.

bell hooks talks to John Perry Barlow→

John Perry Barlow: It seems to me that what we’re here to do is to learn about love in the presence of fear.

bell hooks: I have been thinking about the notion of perfect love as being without fear, and what that means for us in a world that’s becoming increasingly xenophobic, tortured by fundamentalism and nationalism. Even about meeting you—the idea of being able to let fear go so you can move towards another person who’s not like you. I’ve never met anyone from Wyoming before.

John Perry Barlow: Much less a Republican cattle rancher.

bell hooks: When we drop fear, we can draw nearer to people, we can draw nearer to the earth, we can draw nearer to all the heavenly creatures that surround us.

John Perry Barlow: I was just describing you to someone in terms of the externalities that would end up on your curriculum vitae, and the person said, she sounds like your polar opposite. On paper, you are my polar opposite and yet I feel none of that in your presence.

bell hooks: I actually feel that my heart was calling me to you. The first time we were in the same room for a prolonged period of time together, I sought you out. I wanted to hear your story.

John Perry Barlow: I felt the same way.

bell hooks: And what I see in a lot of young folks is this desire to be only with people like themselves and only to have any trust in reaching out to people like themselves. I think, what kind of magic are they going to miss in life? What kind of renewals of their beings will they never have, if they think you can have some computer printout that says this person has the same gender as you, the same race as you, the same class, and therefore they’re safe? I feel that intuition is so crucial to getting beyond race and class and gender, so that we can allow ourselves to feel for and with another person.

(…)

bell hooks: I feel that especially when it’s chores I don’t want to do, like taking out the garbage or doing my laundry. It’s in the act of having to do things that you don’t want to that you learn something about moving past the self. Past the ego.

(…)

bell hooks: One of the guiding issues of my life right now is thinking about the difference between being fear-based and faith-based. When we think about the history of science, so much of it is rooted in this quest to find answers that will silence fear.

The Web’s Grain→

Frank Chimero, against the kinds of spectacular design that breaks expectations and experiences :

What would happen if we stopped treating the web like a blank canvas to paint on, and instead like a material to build with?

And on combatting the inescapable feeling of disappointment one gets from having worked too long in the field:

As for me? I won’t ask for peace, quiet, ease, magic or any other token that technology can’t provide—I’ve abandoned those empty promises. My wish is simple: I desire a technology of grace, one that lives well within its role.

Y2K→

Interviewer: The Y2K was a moment where a large number of women were heading these projects…

Margaret Anderson: I was mostly familiar with the federal government agencies, and I was a woman in technology, and really aware that there weren’t many around me. And what I found with Y2K was all of a sudden I’d be in meetings, and so many of the program managers and the project managers were women. And they were there because it was not a good career move to be in Y2K. It was short term. If there were problems, you were going to get blamed for them. You didn’t have the authority to really make the changes. So many people wouldn’t take the responsibility, so all of a sudden there were a lot of women around, and I saw an unprecedented level of cooperation and information sharing… really. It was beautiful. (audience laughs/claps).

Everything I know about a good death I learned from my cat→

Sadness and grief come differently for animal and human deaths. Grieving a dead human brings so much regret, takes so much time and apathy. With animals, there’s never anything that could have been left unsaid.

Forced to be “Charlie”→

A high school teacher:

As for laïcité, I fear it is becoming a tool that could be perceived as islamophobic by these kids. It was once used as a tool to protect the Republic from obscurantism of country priests. Now I feel it’s used by a part of the population – not the majority – to say ‘Your religion is very nice but you can’t express it the way you want.’

There will not be a Singularity. I think that artificial intelligence is a bad metaphor. It is not the right way to talk about what is happening.

The more I think about it, the more I think that “apps” are a bad unit of organization of software.

Of persona, surveillance and the wild→

This is the feeling, sadly rare, of no longer being watched. The psychotherapist Carl Jung, after seeing a photo of the Arctic explorer Augustine Courtauld, remarked that Courtauld’s was the face of a man ‘stripped of his persona, his public self stolen, leaving his true self naked before the world’. For women, this is doubly true: a woman’s life is one lived under surveillance, a system of inner and outer regulations even more restrictive than a man’s. Even a simple stroll down the sidewalk becomes an exercise in self-loathing. Suck in your stomach. Straighten your hem. (What if it rides up, exposing you?) Every shop window offers a glimpse of your own reflection. Adjust, adjust, adjust.

It’s enough to drive a woman crazy (and isn’t this what we’re always being accused of?). It’s enough to drive any woman to the woods.

What the Theory of “Disruptive Innovation” Gets Wrong→

Jill Lepore, on the spread of innovation bullshitism:

Most big ideas have loud critics. Not disruption. Disruptive innovation as the explanation for how change happens has been subject to little serious criticism, partly because it’s headlong, while critical inquiry is unhurried; partly because disrupters ridicule doubters by charging them with fogyism, as if to criticize a theory of change were identical to decrying change; and partly because, in its modern usage, innovation is the idea of progress jammed into a criticism-proof jack-in-the-box.

Also:

Disruptive innovation as an explanation for how change happens is everywhere. Ideas that come from business schools are exceptionally well marketed.

Soberingly:

Disruptive innovation is a theory about why businesses fail. It’s not more than that. It doesn’t explain change. It’s not a law of nature. It’s an artifact of history, an idea, forged in time; it’s the manufacture of a moment of upsetting and edgy uncertainty. Transfixed by change, it’s blind to continuity. It makes a very poor prophet.

Now, who benefits from the frenzy?

DE$IGN

Is design humility possible today? Can we build a relevant design practice that produces meaningful, rich work — in a business context — without playing to visions of excess?

Index cards→

Jeremy Keith, again:

These days, browsers don’t like to expose “view source” as easily as they once did. It’s hidden amongst the developer tools. There’s an assumption there that it’s not intended for regular users.

Fuck that. I’m more of an editor than a developer any day, but I’ll be damned if I’m going to cede that territory. I don’t want to pour my words into a box, the parameters of which someone else decides (and obscures). I want to make the box, too. And remake it. And, hell, break it from time to time. It’s mine to break.

Programming Sucks

That’s your job if you work with the internet: hoping the last thing you wrote is good enough to survive for a few hours so you can eat dinner and catch a nap.

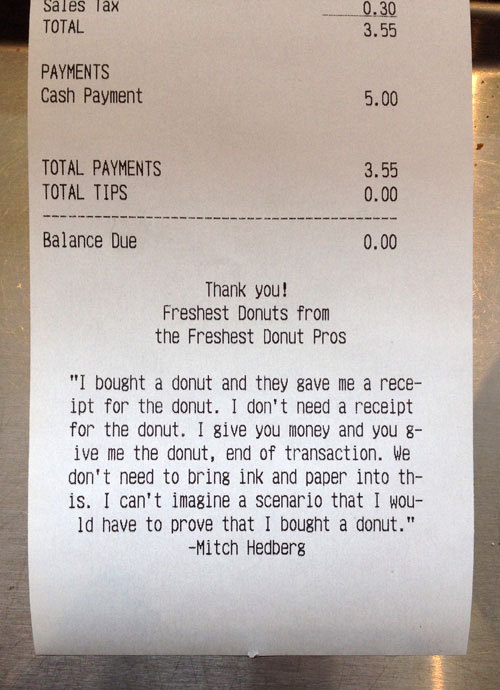

I can imagine tons of scenarios where I would have to prove that I bought a donut, actually.

Making Games in a Fucked Up World→

Pretty much sums up why I’m weary of the phrase “user experience design”:

If you actually figure out methods to control people’s behavior. You can bet they will be adopted by governments and advertisers in no time. You are working for them.